Claudia Jones was one of the most influential Black woman thinkers and leaders of her time, whose theories and politics have shaped the world in ways most fascinating and unimaginable. The importance of her contributions to Black liberation movements, in the UK, US, and elsewhere, is extremely and severely underappreciated, and many of those without an extensive grounding in Black feminist/communist/liberation theory will have, unfortunately, never heard of her. Fortunately,thanks to the internet and social media more and more of us are becoming aware of the magnificent work of the illustrious Claudia Jones.

Early life, death of her mother, and high school

Born as Claudia Vera Cumberbatch on February 21st, 1915 in Belmont, Trinidad & Tobago, she migrated to Harlem in the US with her parents in 1924, following the crash in the price of cocoa following the First World War. Early life in America for Jones and her family was extremely difficult; the premature death of her mother five years after arriving forced her to temporarily drop out of school and take up factory work in order to help supplement her family’s low income. Due to the poor living conditions she had, she contracted tuberculosis in 1932 and, though she survived it, this terrible illness caused permanent damage to her lungs, the effects of which affected her all throughout her adult life.

Despite being an erudite high school graduate, her position as a Black, Caribbean immigrant woman in a pre-civil rights United States was evidently restricted, and she could only find employment in a launderette, and subsequently, in retail. Claudia Jones’ first hand at writing for a publication came in the form of a column, named Claudia Comments, for the National League on Urban Conditions Among Negroes (now simply known as the National Urban League), whose drama group she was a member of.

The Scottsboro Boys, the CPUSA, and An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman!

The infamous Scottsboro Boys case in 1930s Alabama caught the attention of the whole country. The Scottsboro Boys were nine Black teenagers who were falsely accused by two white women of rape during a train journey between Chattanooga and Memphis, Tennessee. In the first case in 1931, eight of the nine teenagers were convicted and thus sentenced to death, which was the common sentence in Alabama for a Black man found guilty of raping a white woman. Jones’ determination to support the cases of these teenagers brought her into contact with the Youth Communist League USA, the youth wing of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA), of which she became a member in 1936. Following huge pressure from CPUSA (as well as the NAACP and other bodies), after a protracted battle involving several retrials and an intervention from the US Supreme Court, all nine avoided execution, but five of them still unjustly served jail time.

The nine Scotsboro Boys who were falsely accused of raping two white women in 1931

She remained heavily involved in CPUSA for almost two decades, as an organiser, leader, editor, theoretician, and journalist. She adopted the surname “Jones” as “self-protective disinformation”; a protective measure against McCarthyism and its associated persecution of communism and its sympathisers. After World War II, she was elected to the National Committee of CPUSA in 1948, and shortly afterwards, became the Secretary of Women’s the Women’s Commission in the party.

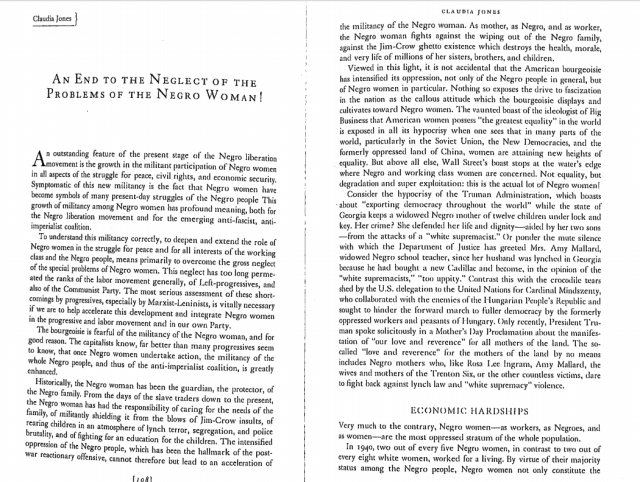

In her years in the US, Jones proved her status as a one of the most important Black feminists in history, whose sharp mind and incisive analyses paved the way for many like her who came after her in the decades that followed. In 1949, she published her best known piece, “An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman!”, in which she shows an exceptional appreciation for the inextricable link between her race and gender. She was a pioneer of what we would now categorise as “intersectional” thought. The following is an extremely powerful extract from her analysis of the necessity to value the importance of Black women in Black liberation movements, and how understanding the uniqueness of the oppression Black women faced would allow a more nuanced comprehension of the oppression of the community as a whole:

“The bourgeoisie is fearful of the militancy of the Negro woman, and for good reason. The capitalists know, far better than many progressives seem to know, that once Negro women begin to take action, the militancy of the whole Negro people, and thus of the anti-imperialist coalition, is greatly enhanced.

Historically, the Negro woman has been the guardian, the protector, of the Negro family…. As mother, as Negro, and as worker, the Negro woman fights against the wiping out of the Negro family, against the Jim Crow ghetto existence which destroys the health, morale, and very life of millions of her sisters, brothers, and children.

Viewed in this light, it is not accidental that the American bourgeoisie has intensified its oppression, not only of the Negro people in general, but of Negro women in particular. Nothing so exposes the drive to fascization in the nation as the callous attitude which the bourgeoisie displays and cultivates toward Negro women.”

An extract from the first two pages of An End to the Neglect of the Problems of the Negro Woman, Claudia Jones, 1949

Prison sentence and deportation from the US to the UK

Despite her best efforts, the FBI had been tracking her involvement with CPUSA for a long time, and this led to several arrests and four separate spells in prison, the first of which was spent on Ellis Island in 1948. Jones was found guilty of violation of the McCarran Act, as she was a non-US citizen (“alien”) who had joined the Communist Party USA, and the first date for her deportation was scheduled for 21st December, 1950. While being held in prison during her prosecution in the course of the separate Smith Act trials (prosecution of suspected communist leaders), Jones suffered her first heart attack in 1951, at the age of 36. She was later convicted in the Smith Act trials for her “un-American activities”, and served an eight month sentence at the Federal Reformatory for Women at Alderson, West Virginia in 1955, after which she was deported to the UK on 7th December of the same year, after being refused entry to Trinidad & Tobago by the British colonial governor, Hubert Rance, who claimed that “she may [have] prove[n] to be troublesome”.

Engagement with Black British movements during the Civil Rights Movement in the UK, The West Indian Gazette, and Notting Hill Carnival

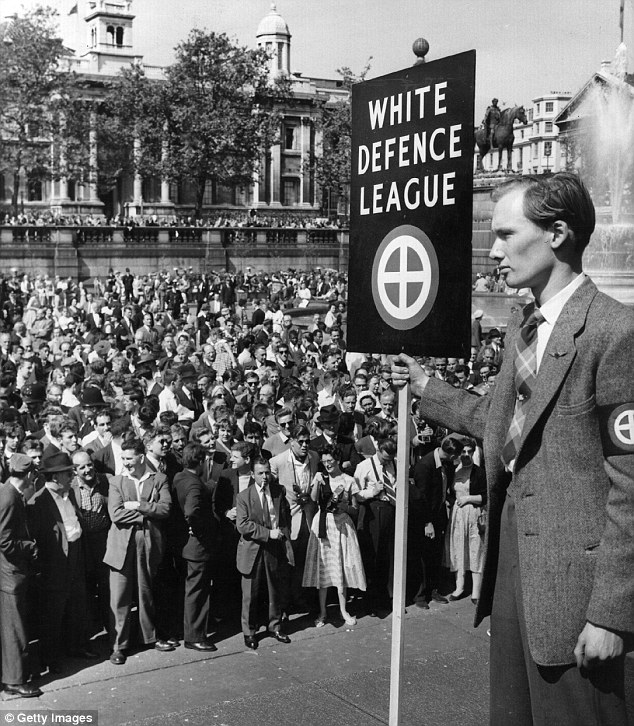

Upon arrival in Britain, Jones was disappointed by the racist hostility shown towards her as a Black woman in British communist circles. She was also horrified by the ubiquitous “No Irish, No Blacks/Coloureds, No dogs” policy that many landlords, shop-owners, and even government institutions adopted used in pre-civil rights Britain. The arrival of Caribbean people of the Windrush Generation also saw the rise of the White Defence League, started by Colin Jordan. The White Defence League, which was influenced by the earlier rhetoric of Sir Oswald Mosley and his British Union of Fascists, was a white nationalist and neo-Nazi movement seeking to “Keep Britain White” by any means necessary. Upon realising that, like America, the UK was the furthest thing from what could ever be perceived as a paradise for Black people, Jones began engaging extensively with the Afro-Caribbean community almost instantly.

![8b5c76c6f638b75b25d11df99ba6fe12[2]](https://everlivingroots.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/8b5c76c6f638b75b25d11df99ba6fe122.jpg?w=640)

This was a common sight for many black families on their front doors.

The White Defence League assembled in Trafalgar Square on March 24th, 1959, preaching violence and racist hatred against Black people in Britain

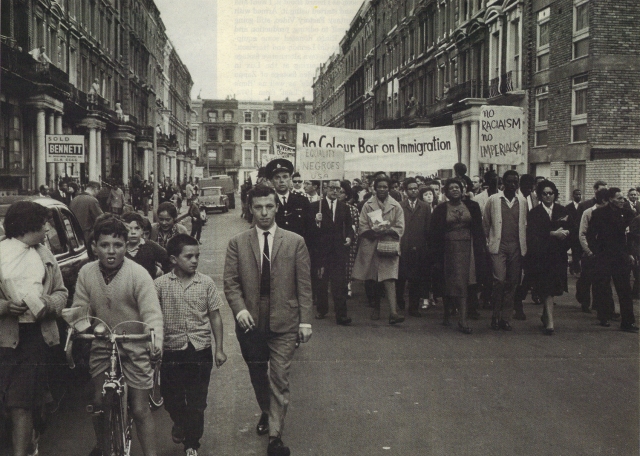

Claudia Jones openly campaigned for equal access to basic services, such as housing and education, and openly denounced the racism exercised in the employment market, and lobbied against Britain’s racist Immigration Act of 1876. Her huge influence, as well as that of her collaborators, such as W.E.B Du Bois, Trevor Carter, Nadia Cattouse, Amy Ashwood Garvey (the first wife of Marcus Garvey), Beryl McBurnie, Pearl Prescod, and her lifelong mentor Paul Robeson, was pivotal to ensuring the progress of the British Civil Rights movement in the 1950s and 60s.

Claudia Jones (pictured centre in grey jacket) leads an anti-racist, anti-imperialist march in London

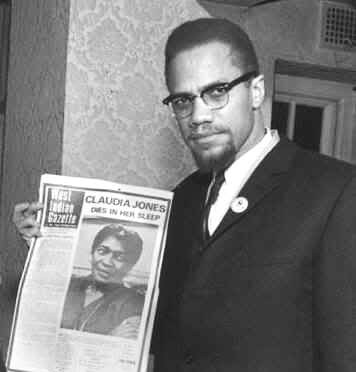

Jones can be famously quoted as saying, “people without a voice were as lambs to the slaughter,” and by these words did she certainly live. In 1958, on 250 Brixton Road in Brixton, SW9, London, she set up The West Indian Gazette, an anti-imperialist and anti-racist publication, to provide Caribbean people within Britain with the voice they needed to seek their liberation. Increased consciousness within the British Afro-Caribbean community is credited to Claudia Jones and her monthly West Indian Gazette, which had a circulation of around 15,000 at its height. In 1964, in the last published essay of hers prior to her death, Jones wrote the following for Freedomways, a Black American journal founded by Louis Burnham, Edward Strong, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Shirley Graham Du Bois:

“The newspaper has served as a catalyst, quickening the awareness, socially and politically, of West Indians, Afro-Asians and their friends. Its editorial stand is for a united, independent West Indies, full economic, social and political equality and respect for human dignity for West Indians and Afro-Asians in Britain, and for peace and friendship between all Commonwealth and world peoples.”

Malcolm X with a copy of Claudia Jones’ West Indian Gazette

Despite its swiftly growing popularity, The West Indian Gazette struggled with financial issues from its inception, which only worsened following the death of Claudia Jones, and it ceased publication in August 1965, eight months after her passing.

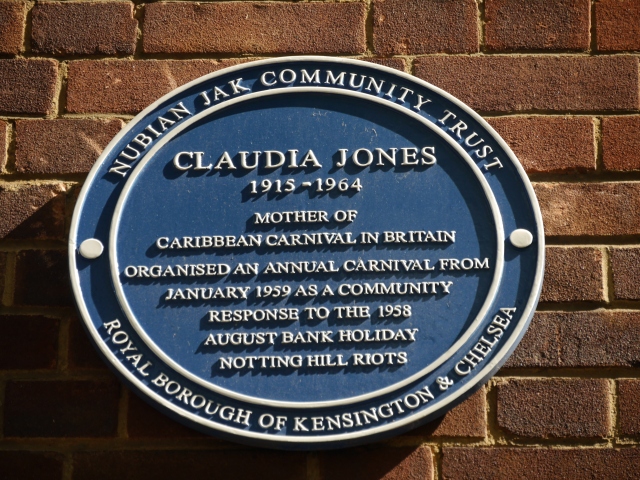

Four months after the first issue of The West Indian Gazette, racial tensions reached a spearhead, resulting in the days of protest and unrest between racist whites and the Black community in Notting Hill in August 1958. The Black British community, as well as Caribbean leaders, such as Norman Manley and Eric Williams, turned to Jones for help and guidance during this period of heightened public, racially-driven animosity towards Black people in the UK. She therefore decided that there should be a carnival for the West Indian community, which would serve as an empowering and cathartic solution – this developed into what we now recognise as Notting Hill Carnival (read more on this history here). These celebrations were broadcast on the BBC, and the slogan of this predecessor to Notting Hill was as follows – “A people’s art is the genesis of their freedom.”

Death and legacy

Suffering from ailing health due to her childhood health complications with tuberculosis, Claudia Jones sadly passed away due to a severe heart attack on December 24th, 1964 in England, and was found at her flat on Christmas Day. Her death was deeply saddening and sent shockwaves throughout the Black community, both in Britain and internationally. Her funeral was large and it took place on 9th January, 1965, at which an obituary sent from Paul Robeson was read:

“It was a great privilege to have known Claudia Jones. She was a vigorous and courageous leader of the Communist Party of the United States, and was very active in the work for the unity of white and coloured peoples and for dignity and equality, especially for the Negro people and for women.”

She is currently buried to the left of Karl Marx, from whose work she developed many of her own theories, in Highgate Cemetery in North London.

Plaque commemorating Claudia Jones in Notting Hill

Claudia Jones’ legacy is a testament to how influential she was as a Black feminist, political theoretician and leader. A Claudia Jones Memorial Lecture is held annually by The National Union of Journalists’ Black Members Council in the UK, during Black History Month, in honour and respect of her ground-breaking work and activism. The Claudia Jones Organisation was founded in 1982 in London to both empower and provide the voice to women and families of Afro-Caribbean heritage all over the UK; a voice whose importance Jones centred so much in her work.

Her place in history is well-defined and well-earned. Let us never forget the incredible contributions of Claudia Jones to Black liberation movements worldwide, of years past, present, and, undoubtedly, of those in future.

Sources:

https://blackfeministmind.files.wordpress.com/2009/03/claudiajones.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Smith_Act_trials_of_Communist_Party_leaders

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Claudia_Jones

http://caribbeanreviewofbooks.com/crb-archive/16-may-2008/excavating-claudia/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scottsboro_Boys

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Urban_League

https://socialistworker.co.uk/art/2810/Claudia+Jones%3A+the+black+Communist+who+founded+the+carnival

http://www.aaihs.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Claudia-Jones.jpg

http://www.voice-online.co.uk/sites/default/files/imagecache/455/Claudia_Jones_web.jpg

http://www.religiousleftlaw.com/patrick-s-odonnell/

http://www.irr.org.uk/news/claudia-jones-and-the-west-indian-gazette/

5 thoughts on “The Story of Claudia Jones – A Pioneering Black Feminist, Political Leader, and Educator”