Haitian Vodou (or Voodoo, as it is often spelled in Western accounts) is no doubt one of the most interesting religions known to the world. A religion, whose roots lie firmly in ancient West African thought, has inseparable ties with the cultural heritage and history of Haiti. Vodou, as well as its practitioners, have unfortunately suffered centuries of ugly stereotyping and open persecution, caused by the widespread efforts of white, Catholic colonists to stigmatise them, as they feared the idea of Africans in Haiti getting involved with African spirituality. Due to this, many myths and misconceptions about Vodou still exist today. Yet, the intriguing truth and history of Vodou has lived on through this.

Vodou – A Brief History

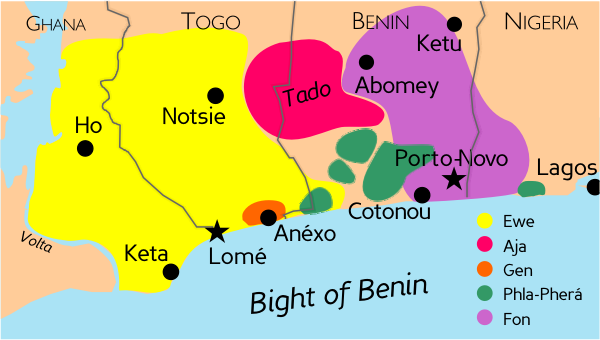

A large number of enslaved Africans brought to Haiti in the 1700s, known as Saint-Domingue before the Declaration of Haitian Independence on 1st January, 1804 by Jean-Jacques Dessalines, were from the Kingdom of Dahomey in West Africa, which was located in what is now known as Benin. The word Vodou derives from the word Vodu in the eponymously named language of the Fon people of West Africa; Vodu means “god” or “spirit”. Haitian Vodou developed syncretically in the 18th century; being primarily influenced by West African Vodun (practised by the Fon and Ewe), it also grew with aspects of Yoruba and Kongo culture and beliefs, along with those of the autochthonous Taíno people of Haiti, and was also influenced by elements of European beliefs, including Roman Catholicism brought by slave owners.

Areas known to practise West African Vodun

Practitioners of Vodou, known as Vodouisants, believe in a Supreme, unreachable God, known as Bondye, from the French bon dieu, meaning “good God”. The Lwa/Loa (from the French lois, meaning “laws”), also known as the mistè (mystères in French), are Vodou spirits, and serve as the necessary conduits between Vodouisants and Bondye. While the Lwa are not actually classed as deities, Vodouisants still serve and pray to them. As time passed, associations between Haitian figures (Bondye and the Lwa) and those of Roman Catholicism (God and saints) were made often, highlighting how many practitioners of Vodou follow a more syncretic adoption of the religion. The Lwa are divided into nations (nanchons) and families, each in charge of different aspects of life.

Examples of Lwa:

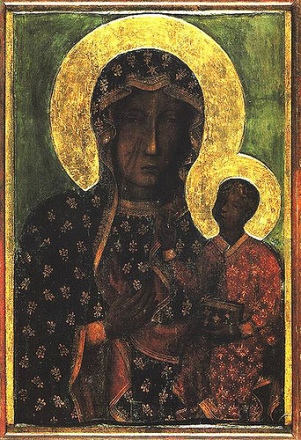

Petwo: the Petwo nation of Lwa are considered war-like. A notable Lwa is Ezili Dantor, a dark-skinned black woman modelled on a warrior of the N’Nonmiton, meaning “our mothers” in Fon, which was a female-only regiment of the army of the Kingdom of Dahomey. She is associated with the now extinct Creole pig of Haiti, one of which was sacrificed to Ezili Dantor during Bois Caïman, the famous, and arguably the most important, Vodou ceremony, which is often marked as the start of the Haitian Revolution, on August 14th, 1791, being the only successful insurrection of enslaved people leading to an independent state.

Depiction of Ezili Dantor, whose face is distinctively scarred from battle

Guédé: the spirits of the Guédé family represent death and fertility. A notable Lwa from this family is named Guédé Nibo, a spirit of an effeminate, young man, who was killed in a horrific manner. Nibo is a psychopomp, one whose responsibility is to escort newly deceased souls to the afterlife, and provides patronage to the (sometimes lost) souls of those who also died at a young age; it is for this reason that he is often syncretised with the Roman Catholic saint, Gerard Majella. He also has a selection of chevals, or horses, which search for the souls still stranded “below the waters”.

Nago: this nation comprises Ogun, the Yoruba Orisha, who is a warrior and a skilled metalworker. Ogun is often noted as the first Orisha to enter the realm of Earth, in order to secure a home for human life; he is still working towards this goal.

Artist’s impression of Ogun. Source: The Art of Stephen Hamilton/Tumblr

Persecution of Vodou

In the years following the Haitian Revolution, no countries would officially recognise this new state of Haiti. The country suffered from boycott and isolation, and was under trade embargoes enforced by major forces in the global market. With France imposing its unjust and crippling 150 million Franc debt upon the country, quoting a “loss of property” following the Haitian Revolution, a large number of people aimed to distance themselves from Vodou and severed any ties to the culture deemed to be “rebellious” by white Europeans. In 1835, ten years after the imposition of debt, the government in Haiti forbade people from being practitioners of Vodou; Vodouisants were thus driven underground, into secret, spiritual support groups, all of which developed their own codes to prevent detection, and helped maintain a communitarian unity during times of turmoil.

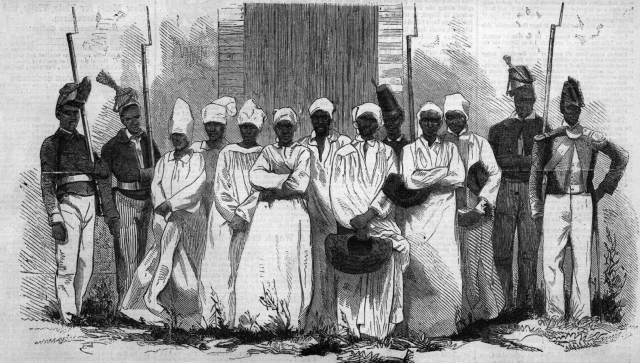

The most notable attack on Vodou came from within the country, in 1864. It was the Affaire de Bizoton, a high profile case, at the end of which four men and four women were executed for the abduction, murder and cannibalising of a 12-year-old girl, apparently driven by their adherence to the folk religion. The French-educated ruling class, alongside poorer communities, assembled under the declaration of the President, Fabre Geffrard, in the Haitian capital, Port-au-Prince, on Saturday, February 13th, 1864, to witness this execution. Geffrard was determined to “reform” the country – to move it away from what he perceived to be its “decadent” and “backward” African roots and religion, and used this as a perfect pawn in his propaganda machine. The case was shrouded with malpractice and biased reporting, and it came to light that confessions obtained from the condemned eight were fraudulently obtained through torture.

The eight Vodouisants condemned to death after being questionably found guilty of abduction, infanticide and cannibalism in 1864

White people in the US had heard news of the successful revolt in Haiti and were extremely afraid that it would empower and inspire enslaved Africans to stage similar uprisings on their plantations. They feared the Vodou deities, as they saw how the religion inspired Haitians to fight for their freedom, so an aggressive move to vilify and debase it was adopted across the whole of America. Contemporary media began to introduce what are now the modern stereotypes associated with Vodou: barbaric; a satanist affront to (Christian) holiness; the ability to curse someone by sticking pins in scarily-fashioned dolls; and blood-drinking savages chanting around fires. After a trip in 1899, British traveller Hesketh Hesketh-Pritchard had utter disdain for the culture, describing the religion as simply “West African superstition serpent worship,” whose practitioners engaged in “their rites and their orgies with practical impunity.” So ingrained is the prejudice against Vodou that Pat Robertson, an American evangelist priest, stated that the devastating 2010 Haiti Earthquake occurred as a result of the country’s “pact to the devil” at Bois Caïman over 200 years ago in 1791 at the advent of the Haitian Revolution.

Final Thoughts

Throughout its centuries of existence, Haitian Vodou has provided inspiration, spiritual and physical empowerment, and solace to many Africans. Among attempts to ridicule and demonise its importance to many Haitian people, Vodou is inextricably linked to Haitian culture and represents a beautiful blend of its history and heritage, and continues to be maintained in various forms by Vodouisants across the world, particularly in Louisiana and other Caribbean countries. When one delves into the true story of Vodou, it does not tell the old tale of evil witchcraft and devil worship; it instead evokes the wonder of, and interest in, a historically and religiously significant part of African diasporic history.

Sources:

The Esoteric Codex: Haitian Vodou – Garland Ferguson

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haitian_Vodou#/media/File:Affaire_de_Bizoton_1864.png

upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/0/03/Gbe_languages.png

farm4.static.flickr.com/3185/3082769724_d135ef498b.jpg

http://mashable.com/2015/10/11/haiti-voudou-voodoo-photos/#EfWtp6Is8kqV

upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ef/Affaire_de_Bizoton_1864.png

http://www.univie.ac.at/Anglistik/webprojects/LiveMiss/Voodoo/chap1.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loa

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Haitian_Vodou

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dahomey

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ezili_Dantor

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/nov/07/vodou-haiti-endangered-faith-soul-of-haitian-people

http://www.univie.ac.at/Anglistik/webprojects/LiveMiss/Voodoo/chap1.htm

http://ufdcimages.uflib.ufl.edu/AA/00/01/50/46/00002/Vodou%20Whole%202013_Secured.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychopomp

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ogun

http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-trial-that-gave-vodou-a-bad-name-83801276/?no-ist=

2 thoughts on “Haitian Vodou – Complex and Misunderstood”